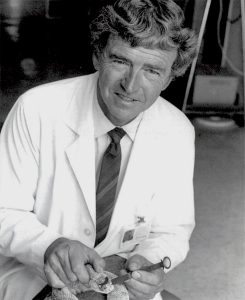

Spiders and C.S. Lewis With Findlay E. Russell ’51, PhD

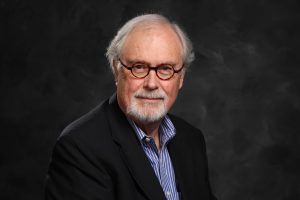

By Dennis E. Park ’07—HON, MA, Consulting Historian

This article is a précis of “Dining at the High Table: Dr. Findlay E. Russell’s Extraordinary Life and Passing Friendship with C. S. Lewis,” pending publication by the author. Quotations in this article are either from the notes taken by the author during his conversations with Russell or Russell’s personal notes, which he gave to the author in 2006.

On Saturday evening, October 20, 1962, a continent away from his laboratory in Los Angeles, California, Findlay E. Russell ’51, PHd, a scientist/physician, stood in a noisy, musty, smoke-filled cloakroom adjacent to the grand 16th-century [dining] Hall located at Magdalene (Mawd-lin) College, a constituent institution to Cambridge University. Russell was not alone. He along with his host, Professor George (Morgan) Hughes, MA, PhD, and ScD (1925–2011), a neurophysiologist, and other men of letters—all (including Russell) were wearing their academic regalia to this invitation-only dinner—waited for the dinner gong to sound announcing that the dining Hall doors were open.

While on academic leave from his responsibilities as director of the Laboratory of Neurological Research at the Los Angeles County General Hospital, Russell would be “attached” to the College of Physicians as a “visiting scholar and scientist” for the 1962–1963 academic year. Having arrived on campus only weeks before, Russell was in the throes of assimilating the traditions of Magdalene College when he received the dinner invitation. Now he had to be concerned with proper dining etiquette as he enjoyed a delicious meal with the eminent Cambridge professors and scholars, which on occasion was attended by C. S. Lewis who had a standing invitation. And so, Russell nervously stood in the cloakroom waiting for the gong to sound.

Suddenly, all conversation and laughter ceased. Professor C. S. Lewis had entered the room in his customary rumpled slacks, tweed jacket, and overcoat. He disliked the pomp and circumstance the academic robes presented. As he removed his overcoat, Lewis greeted nearby colleagues, including professor Hughes, who introduced Russell as a professor at the College of Medical Evangelists in Loma Linda, California. With his distinctive booming voice, Lewis declared, “Gracious, I hope he won’t try to evangelize us all.” Russell recalled, “Lewis’ loud retort generated laughter among the guests.” Hughes continued by telling Lewis, “Professor Russell will be working with me in the department of zoology.” As Lewis was known to do, he “took control of the conversation.”

Lewis: “You are not one of those vivisectors, are you?”

Russell: “I am, perhaps, but I try never to sacrifice life without cause and compassion.”

Lewis: “And how does one determine cause?”

Before Russell could answer, Lewis asked: “I hear you work with spiders and actually handle the little beasts, I am told. Tell me, how do you handle a spider?”

Russell: “I pick up a spider while it was under an anesthetic and I milked it.”

Lewis: “Milked it?”

Russell: “Yes, the process of getting venom out of a spider is called ‘A Milking.’ It is done electrically.”

Lewis: “My gracious.”

Much to Russell’s delight, Hughes had arranged for him to sit at [the] “High Table” with professor Lewis. Russell was “impressed with Lewis’ vigorous imagination. Most of our one-on-one conversation centered on animals, particularly their behaviors, rights, and other related matters.” This encounter with Lewis would not be Russell’s last.

His notes reflect that he met with Lewis numerous times. Russell recalled “times when he and Lewis sat in well-worn, overstuffed chairs, warming their feet before a small electric fire.” By December 19, 1962, however, Russell recalled that “Lewis was not looking well. His gait was slow and somewhat labored.” Two of Lewis’ confidants and colleagues summoned Russell to “look in on Lewis, who was unwell—and not following his personal physician’s orders.” Russell’s final meeting with the ailing Lewis was between June 6-12 (the exact date is lost to history). Lewis’ death on November 22, 1963, would be overshadowed by the assassination of the U.S. President, John F. Kennedy, on that same date.

Who was Findlay Ewing Russell, whose notes reveal a “passing friendship” with C. S. Lewis? To many, Russell was an enigma. He asserted that in school he “majored in extracurricular activities.” He readily admitted that he was not a good student. He attended three colleges. The second, La Sierra College, expelled him and a few other mischief makers for a practical joke that didn’t resonate with the college administrators. He graduated from Walla Walla College and soon found himself in World War II, bogged down on the battlefields in the South Pacific. There, his hands and fingers were severely maimed. After many surgeries and several months of rehabilitation, the young Army veteran began to think about his future. Findlay recalled, “Medicine was kind of in the back of my mind, but the thought of my extracurricular activities, less than stellar grades, and the lack of needed prerequisites seemed counterintuitive to reality.”

Though determined to try medicine, Russell enrolled at the University of Southern California (USC), where he took the remaining prerequisites, resulting in a better overall GPA. He applied to medical school at USC, where he was accepted and given a small scholarship. At about the same time, he was having recurring issues with his war injuries. At the recommendation of a family friend, a CME graduate, Russell transferred to CME in Loma Linda, where he was told there was an “excellent hand surgeon” on the faculty. Due to Russell’s outgoing personality and his ready wit, the new arrival quickly made friends. However, with Russell, old habits were hard to break. In his mind, friends meant fun, and before long, his extracurricular activities were getting in the way of his studies. Russell recalled being ushered in to the dean’s office where Walter E. Macpherson 1924, looked at him and said, “Findlay, I am worried about you.” Without another word, the gentle dean dismissed the stunned medical student who had expected to be expelled. This bitter pill administered by the kindhearted Dean Macpherson was a “seminal moment in my life,” Russell recalled. “Later he became my mentor and then my lifelong friend.”

Following his internship at the White Memorial Hospital and the LA County Hospital, the young doctor was expected to take a residency program. Russell had other plans. Due to his inquisitive nature, he had grown to appreciate the exactitudes of research science while spending valuable hours in the laboratories of Cyril B. Courville 1925, who was a widely respected neurologist, author, and founder of the Cajal laboratory at the Los Angeles County Hospital.

With a highly favorable recommendation from Macpherson, he was offered a two-year fellowship with (Anthonie) Van Harreveld, MD, (1904–1987) a distinguished Caltech neuroscientist. During his tenure at the Caltech laboratories, the young budding research scientist regularly rubbed shoulders with some of the giants in the field of science, William B. Shockley, PhD, [1910–1989], a physicist, inventor, and a 1956 Nobelist. While there, Russell worked with intellects soon to become Nobelists: Richard Feynman, PhD [1918–1988], a Caltech theoretical physicist and a 1965 Nobelist; Max Delbruck, PhD, [1906–1981], a specialist in genetics and biochemistry and a 1969 Nobelist; and Linus Pauling, PhD, [1901–1994], a chemist, biochemist, and chemical engineer and a 1954 and 1962 Nobelist. Russell said of this experience, “It was not until I went to Caltech to work with Linus Pauling and others that my enthusiasm was kindled, and I finally began to find my niche. I could almost feel the synapses sparking, and every pursuit seemed exciting.”

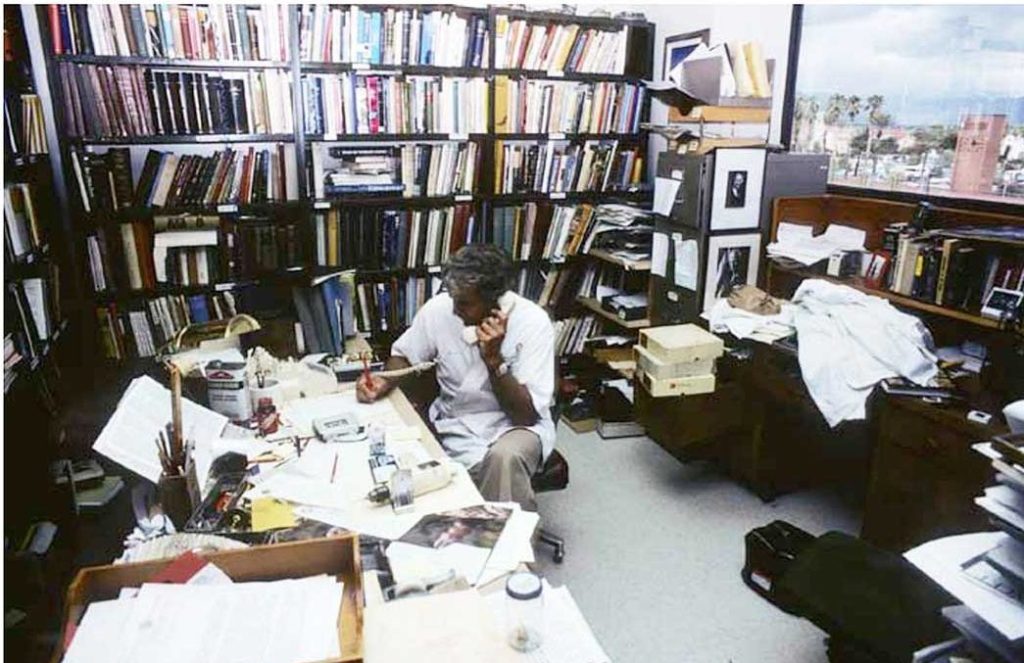

Upon returning from Magdalene College, Russell continued his research at the Los Angeles County General Hospital Laboratory of Neurological Research. In 1981, he transferred his laboratory to the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center, department of pharmacology and toxicology. There in his research labs, professor Russell continued his research until he reluctantly, due to ill health, put aside his beakers, pipettes, Petri dishes, and laboratory notebooks. He passed away on August 21, 2011, just a few weeks before his 92nd birthday.

During his career, Russell authored nine books (many of which are referenced in ER’s around the globe), authored over 300 peer-reviewed articles, and edited numerous academic and scientific journals. Russell was a much-sought lecturer and consultant to foreign governments, including NASA and WHO. In his spare time, he had many visiting appointments. In addition, Russell was a 1976 Fulbright Scholar and visiting professor at Józef Stefan Institute, Ljubljana University, Yugoslavia. He was an inventor who held several medical patents. In addition, Russell, along with John Sullivan, MD, developed CroFabTM, the first antivenin of its kind to be approved in over 50 years, which is a purer product to combat snakebites. In 1962–1963, Russell co-founded the International Society of Toxicology and was the first editor of its journal, Toxicon. Both the society and journal have grown exponentially. As of 2024, the Society has approximately 8,000 members, and Toxicon is published monthly for the Society members. In 1987, Russell added to his academic achievements when he received his PhD in Medieval English Literature from the University of Santa Barbara. C. S. Lewis would have been proud.

Published in the Summer 2024 ALUMNI JOURNAL.

Dennis E. Park ’07–hon, MA is the consulting historian for the ALUMNI JOURNAL and former executive director of the Alumni Association. He is also the author of “The Mound City Chronicles: A pictorial History of Loma Linda University 1905–2005.”