World War II, CME, and Letters from the 47th

By Dennis E. Park, MA, ’07-hon, Consulting Historian

“The site chosen for the [47th General] Hospital was not far from the battlegrounds which marked the farthest point of penetration southward by the Japanese troops. Here was the turning point of the war, and also the beginning point for what was perhaps the most unusual venture of any Christian medical college.”1

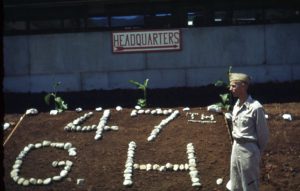

In 1943, during the height of World War II, a unique confluence occurred that would endure until the end of the war. The College of Medical Evangelists (CME), with its Los Angeles campus and its Loma Linda campus, added a unique “third campus”: the 47th General Hospital (47th), a field hospital located on the island of New Guinea, which, “for the first time in history,” offered “the nation at a time of great need … a large hospital.” Though this campus did not train medical students, it served, in a sense, as an extension of CME on the other side of the world. “Every medical officer at the time [the 47th] was activated by the Army was a graduate of our medical college [CME]. And about one third of its nurses were from our various sanitariums.”2

In 1943, during the height of World War II, a unique confluence occurred that would endure until the end of the war. The College of Medical Evangelists (CME), with its Los Angeles campus and its Loma Linda campus, added a unique “third campus”: the 47th General Hospital (47th), a field hospital located on the island of New Guinea, which, “for the first time in history,” offered “the nation at a time of great need … a large hospital.” Though this campus did not train medical students, it served, in a sense, as an extension of CME on the other side of the world. “Every medical officer at the time [the 47th] was activated by the Army was a graduate of our medical college [CME]. And about one third of its nurses were from our various sanitariums.”2

Seventy-five years after the war ended in 1945, we reexamine the story of the 47th General Hospital. We will briefly review the development of the 47th and then learn something of what it was like to live on the island and of the spiritual lives and medical ministry of those who served. Primarily this perspective comes from two members of the 47th whose letters to family were made available for this article. Other sources include published letters in The Medical Evangelist (ME) and material from “Diamond Memories” and the ALUMNI JOURNAL.

A Brief History of the 47th General Hospital

The relationship between the 47th General Hospital and the College of Medical Evangelists started during the First World War at a most inopportune time for CME. The struggling college had been in operation for less than a decade and shouldered an all but worthless “C” rating. Even so, the school and the Seventh-day Adventist Church “made a studied effort to demonstrate that Adventist soldiers [were] prepared to render needed service.”3 The denomination’s endeavor was short lived, ending with the war’s conclusion in November of 1918.

However, the medical college’s readiness attempt was not lost on some of its young physicians, including Benjamin E. Grant ’20, who “proposed the organization of a stand-by military hospital to be staffed by Seventh-day Adventist personnel, as a gesture of cooperative preparedness in the event of a future war.” Percy T. Magan, MD, ’33-hon, president of CME, took the idea to the U.S. Army, which “arranged for the prospective hospital to be designated as the 47th General Hospital of the United States Army Medical Corps.” The designation “was a carry-over from an army hospital that had existed during World War I” and later been demobilized.4 With the stroke of a pen the 47th “existed on paper.”5

In 1926, organization of the 47th began when CME President Newton G. Evans, MD, ’90-hon “became the commanding officer with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Reserves.”6 Cyril B. Courville ’25 soon succeeded Dr. Evans. Until such time as the unit was needed, the 47th “functioned as a reserve unit” with the intent to train young Adventist men to serve the nation “as ‘medics’ rather than as combat soldiers” in the event of another war.7

Too soon, war again raged. Many young Adventists were eager to put their medical training to service and applied to join the 47th. In the winter of late 1943, the unit was activated and ordered to report to Hammond General Hospital in Modesto, California, where the 47th General Hospital would organize under the leadership of Dr. Grant, newly appointed commandant.8 There they prepared and waited for deployment.

Confidential Deployment

We learn of what it was like to await deployment from one of our letter writers, a young nurse and Pacific Union College graduate: Harriet O. Smith. In a letter to home she wrote: “Tomorrow a group of us go to Camp Stoneman for identification pictures. … Things are humming here and we are getting ready for anything.” She also expressed her love to her parents, writing: “I will be back one of these days the Lord willing. A general hospital only stays overseas for a couple of years, then is sent back for a rest, and change, not for the entire war will we be there. We are going to relieve one who is already there.”9

Though details about the time and location of deployment of the 47th were kept confidential, this last sentence may indicate that Ms. Smith had some knowledge about where the unit would be deployed. She later wrote home giving her parents explicit instructions on how to deal with rumors of the 47th departing the country. “Please be very careful not to mention anything about my leaving [Hammond] at any time even if you hear it is near or think you know. … We cannot be too careful.”10

Life on the Island

The 47th was soon deployed and, in early 1944, arrived by ship to Milne Bay, located on the southeast corner of the island of New Guinea, just north of Australia. For these medical professionals from the United States, daily life at Milne Bay was different from home in many ways. After arriving at the post, our second primary source of letters, ophthalmologist Paul V. Yingling ’38, wrote: “No news but will write a short note and enclose the pictures of the celebration on the ship. Haven’t had time to leave camp yet and look around.”11 Two days later he’d had time to explore their new home and wrote: “I am in New Guinea. Our tent is quite livable now. We have a good place built to hang our clothes, some shelves, a table, stools, and wash stand.”12

Apparently the letter passed the censor’s watchful eye for Dr. Yingling also told of climbing “up over a ridge and down the other side when we came upon what had been the scene of a battle. Saw a couple of pill boxes which had been wrecked by mortar shells. … When we got back from our hike, we asked our unit censor what he thought about mentioning the evidences we saw of a fight and he said he thought it would pass.”13

Some days were slower than others for the medical staff of the 47th, and the island environment afforded them interesting diversions when time permitted. In a letter written February 6, 1944, Dr. Yingling lamented that it looked “like a long time before I see any patients.” He went on to report that “yesterday afternoon Howard F. Detwiler ’41 and I went to look over the hospital site then took a walk down a jungle path behind the hospital location. Saw some beautiful tree ferns and all sorts of other types of ferns. It was the most beautiful spot I’ve seen. Saw a large snake about twelve feet long which someone had killed.”

A few weeks after arriving, nurse Smith provides a description of living quarters on the island, writing that hers is “in a nice little open air hut. The walls are made from cocoanut leaves … [with] a roof on top made out of leaves. The whole thing is tied together with grass, and hung on poles. … No nails [are] used. You wonder how it stays together, but it does.”14

Later on, as she was settling into the new normal at a military hospital, nurse Smith wrote home that she was going on night duty the following week. Evidently, allowances were made for social outings as she went on to describe what dating was like in the 47th: “They [the date] have to sign for us when getting us and be armed and then sign us back in when returning us. Just like government property we are. I am so used to going out with all types of guns and being behind barbwire high fence with a guard that I shall be lost if I ever get out of here. We can only go to approved places and on the main roads.”15

In at least three letters, Ms. Smith referred to her friend, a nurse named Jane Brown, who shared a hut with her and knew her parents. In one letter, Ms. Smith wrote, “Jane Brown just walked in with my mail.”16 So impressed with her experience at the 47th General Hospital, nurse Jane Brown took the medical course at CME and became doctor E. Jane Brown ’53-A.

On March 5, 1944, a story unfolded on the high seas under the pretext of “target practice.” The Navy captain and crew were in full dress uniform, but instead of preparing the ammunition, the ship’s captain ordered selected crew to arch their swords as he solemnized the wedding of 2nd Lt. James Carroll Elgin ’40 and nurse Barbara Mercer, both stationed at the 47th. In an ALUMNI JOURNAL article, Lowell D. Kattenhorn ’41 described what happened after the wedding: “Barbara returned for her duty shift, and no one on base was the wiser. Life went on at the base as before. Only now Carroll and Barbara were husband and wife. They knew it although no one else did! For diversion they made ice cream for the staff.”17

Even the perspective of war—both physical and spiritual—was different for those of the 47th. In a letter to the editor of the ME, Capt. Lloyd K. Rosenvold ’36 wrote: “You speak of this great war news from the Pacific area. It is a funny thing that even though we are nearer the war than at home, war news hasn’t the interest to me that it did at home.” He went on to describe his spiritual walk and the “deep interest some of the protestant enlisted men have in health reform and other spiritual matters.”18

Spiritual Matters

To the many Adventist officers and medical personnel of the 47th, such spiritual matters played an important role from the start. Of the activation of the 47th, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, a weekly church paper, reported that “at the Hammond General Hospital, the 47th has had its own church services in the post chapel on Sabbath mornings, with Chaplain Bergherm in charge. … Several of the officers regularly preached in our churches … conducted prayer meetings, assisted in Sabbath School, young people’s meetings, etc. The spiritual tone of the unit is high. … Many of the enlisted personnel have attended our church services on the post Sabbath mornings.”19

Also referring to her time at Hammond, Ms. Smith writes: “We really have so many chances to tell about the Truth here—more than I have ever seen before. Nearly every day, I get asked about SDA’s. I have been asked about the Sabbath twice in the last week and the nurses, ward men, and patients seem anxious to know for this is the first time many have heard of us.”20

On New Guinea, the medical staff were closer than ever to the faraway lands heard about in mission stories. Taking a Sabbath evening in June to write his parents, Dr. Yingling mentions that he

didn’t have a chance to go to church today as it was my turn to be on call. … I missed an unusually interesting meeting conducted by an S.D.A. who is now a member of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (NGAU). His job is to take medical supplies to the various native hospitals. His boat was formerly an S.D.A. mission boat. The native boys who man the boat are S.D.A. mission boys from the Admiralty Islands. It takes him about three months to make the rounds of the various hospitals and frequently he has a chance to visit one of our missions and give them supplies. Now that the Yanks are in the Admiralty Islands the boys are anxious to get home to see their loved ones. They have been gone here since the Japanese invaded the place. The boys sang in church. Would give a lot to have a trip to one of the missions.21

There were more than 500 CME alumni serving in World War II, including many in the Pacific Theater, and a number had the good fortune to cross paths with the 47th.22 Lt. Comdr. Alstrup N. Johnson ’35, relayed a message to the ME that he

had the privilege of visiting the 47th General Hospital. The past two months, I have been located across the bay from our CME Group. It has been a rare privilege to see so many of my friends in one company. Almost every Sabbath, I attend Sabbath School and church services. To get there, I travel about ten miles in a boat and the rest of the way by jeep. At home it was difficult to get to church even when the place of worship was but a block away! I will appreciate the wonderful church privileges more than ever as a result of my sojourn—in the jungle or at sea.23

In another letter to the ME, Lt. [junior grade] Allen E. Shepherd ’44-B wrote: “Imagine my amazement when I found that the 47th General Hospital is only ten miles from my present location. I have been to church there three times, and have met several old friends. … They have a beautiful location on a hill overlooking a bay. Their equipment is excellent. The Navy dispensary here is small, and we refer all major cases and x-ray work up to the 47th General.”24

Medical Work

Those of the 47th were in the Pacific to provide quality medical care to wounded soldiers and civilians, but their letters home spared family and friends the gruesome details of a war hospital. Nonetheless, we glean some interesting insight from our writers.

In a letter from June 26, 1944, Ms. Smith briefly told of the native patients she had encountered. “Our patients are all doing fine—you should see how the appendectomies get around. The same day as they have surgery they go out to the latrine and within four days they are running around all over and doing K.P. [kitchen patrol]. They never have a gas pain or adhesions. They eat anything just as soon as they want it. It certainly is a far cry from the lying around that civilians do and they get along beautifully. Of course hernias stay in bed longer but everyone has to take exercise and keep up their strength.”

In a letter dated October 10, 1944, Dr. Yingling wrote:

These are busy days for me. … Yesterday we ran 43 patients through the eye clinic and also had a pretty good number today. … At present I have two optometrists helping me. They are both on detached service so I won’t be able to keep them. Today a new man entered the department and I’m hoping that he will have the ability to learn to refract. He is supposed to have a high I.Q. Thursday I have to present the cases at our surgery meeting. We will have the meeting in my clinic. Today I found a case of retinitis [pigmentosa], which is a rather rare condition and will use him for one of the cases I present. I’ll present my case with Chorioretinitis from the ward and another one with some tears in the Choroid of the eye.

In a November 18, 1944, letter home, nurse Smith mentioned her gratefulness for a small, but valuable, act while working on the septic surgery ward. “We use so many dressings. I often think of the people who have folded them all and wish they knew how much they are appreciated.”

The End of the War

Life and work advanced steadily for the 47th for about a year and a half until, across the globe in Europe, the Germans surrendered on May 8, 1945. By June, there were signs that the war was winding down in the Pacific Theater as well. Capt. Ewald A. Bower ’40 wrote: “Our work is falling off tremendously and there are rumors afoot that we will be leaving soon. … Last Wednesday we celebrated our first anniversary of operation of this unit overseas. It hasn’t been too bad: in fact, in many ways we have been blessed.” In the same ME issue, it was reported that Maj. Harrison S. Evans ’36 was promoted to lieutenant colonel, one of many alumni medical officers promoted during the war.25

On August 14, the Japanese surrendered. Nurse Smith wrote, “Everything seems like a dream to us here. We cannot realize it is really over. Looks like we may be packed up for another move one of these days.”26

Soon after the surrender, hospital operations halted and the staff were given relocation assignments. Twelve days later, from the Philippines, Marjorie Stiles, RN, penned a letter to Varner J. Johns ’45, wherein she gave him an update on the status of the 47th and its personnel. (Hers is the last known letter published in the ME about the 47th.) “The 47th General Hospital was beginning to build on a lovely location right on the beach when V-J Day came along, so the building stopped and last week the unit moved to a group of buildings vacated by another hospital which is scheduled for Japan. Most of the doctors have been transferred to another hospital—a number of them will be sent to Japan. Eight of our nurses including myself and other non-Seventh-day Adventists were left behind when the larger group moved with the unit last week.”27

On September 11, 1945, Ms. Smith wrote an eight-page letter to her parents: “Well it is all over. I could have signed up for Japan but did not. Are you glad? It will be about 4 months before we leave here at Rosales [a city in the Philippines]. … There have been so many changes of doctors and transfers that it hardly seems like the old unit. Sometimes I get rather homesick for Milne Bay.” Apparently there were stragglers in the Philippines who were unaware the war was over. Nurse Smith went on to describe an unusual incident: “On the 5th of September, I had a patient shot by the Japanese that day just 6 miles from here. A group of 30 Japanese attacked them. They caught two of them but the rest got away. Evidently no one had told them that the war was over.”

In an October 16, 1945, letter to his wife, Ruth Arlene, Dr. Yingling mentioned the fate of the 47th General Hospital and shared his feelings regarding his experience at the base: “The old 47th is entirely broken up and very shortly there won’t be anyone left down south. That entire area of the base is folding up. Sweetie, when I see some of the fellows around here who are going home, I think I’ve done pretty good by Uncle Sam.”

Conclusion

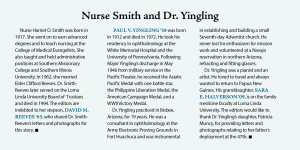

For those who served at the 47th General Hospital in a far-off land, “their mission of mercy and succor, a mission of restoration of both the bodies and souls” was over.28 Via different routes and methods of transportation, they made their way back home where they would practice the art of healing in their individual communities and institutions of higher learning. They would serve and nurture their churches and schools where they lived. Some served in the mission fields at home and abroad. Upon their return to the States, both nurse Harriet O. Smith and Dr. Paul Vernon Yingling made significant contributions to their respective fields of medicine.

In announcing the U.S. Government’s gratitude for the unmeasurable contributions the Seventh-day Adventist men and women health care providers delivered as the 47th, Jerry L. Pettis ’77-hon, then general manager of the Alumni Association, delivered a message from Maj. Gen. Norman T. Kirk, of the Surgeon General’s office, who “expressed the appreciation of the United States Government [with] these words, ‘The excellent cooperation which we received from the College of Medical Evangelists and the outstanding service which was rendered by the 47th General Hospital contributed materially to the exceptional record of the Medical Department. … By its experience and skill it reduced the mortality of our troops to a record unequaled by any nation in the annals of war. … By its valor it won the admiration and respect of all who were entrusted to its care.’”2

Endnotes

1.William H. Bergherm, “How God Used a Hospital,” The Ministry 19, no. 5 (April 1946): 27.

2. Ibid.

3. E. Harold Shryock ’34, “The War Years,” Diamond Memories (Loma Linda: Alumni Association, LLUSM, 1984), 103.

4. Ibid., 103–104.

5. Alonzo Baker, “The 47th General Hospital,” The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald 120, no. 46 (November 18, 1943): 18–20

6. Shryock, Diamond Memories, 104.

7. The War March of CME (Loma Linda: College of Medical Evangelists, 1944), 9; Shryock, Diamond Memories, 104.

8. Shryock, Diamond Memories, 104.

9. Harriet O. Smith (letter), October 27, 1943.

10. Ibid., November 13, 1943.

11. Paul V. Yingling ’38 (letter), February 2, 1944.

12. Ibid., February 4, 1944.

13. Ibid.

14. Smith (Letter), February 25, 1944.[/vc_wp_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_wp_text]15. Ibid., August 11, 1944.

16. Ibid., March 5, 1945.

17. Lowell D. Kattenhorn ’41, “Going Through WWII Together,” ALUMNI JOURNAL 6, no. 2 (March–April 1945): 36–39.

18.The Medical Evangelist 30, no. 23 (June 1, 1944): 20.

19. Baker, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, 18–20.

20. Smith (Letter), November 13, 1943.

21. Yingling (letter), June 2, 1944.

22. Shryock, Diamond Memories, 104.

23. The Medical Evangelist 31, no. 11 (December 1, 1944): 4.

24. Ibid., vol. 31, no. 18 (March 15, 1945): 1.

25. “Capt. Bower of the 47th General Hospital,” The Medical Evangelist 31, no. 23 (June 1, 1945): 1.

26. Smith (Letter), August 15, 1945.

27. The Medical Evangelist 32, no. 7 (October 1, 1945): 1.

28. Baker, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, 18–20.

29. Ibid.

Mr. Park is the consulting historian for the JOURNAL and former executive director of the Alumni Association. He produces www.docuvision2020.com and is the author of “The Mound City Chronicles: A Pictorial History of Loma Linda University 1905–2005.”

Mr. Park is the consulting historian for the JOURNAL and former executive director of the Alumni Association. He produces www.docuvision2020.com and is the author of “The Mound City Chronicles: A Pictorial History of Loma Linda University 1905–2005.”