Sawdust in Her Veins: Sara Witter Connor Tells the Stories of How Wisconsin’s Lumber Industry Shaped the World

By Kim Westerman

Why did three of the most prominent industrialists of the 20th century — Howard Hughes, Sir Geoffrey DeHavilland and Henry Kaiser — come to Marshfield, Wisconsin? Ask Sara Witter Connor, who has had a front-row seat as a family historian of one of the great American lumber families — well, two lumber families, Connor and Roddis.

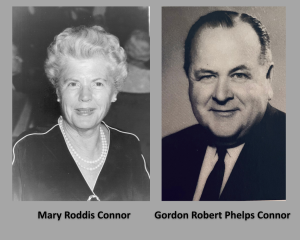

Her parents had a Romeo and Juliet kind of love story. They had grown up together, and when Gordon Robert Phelps Connor asked Mary Roddis to marry him, she couldn’t —because they were in the eighth grade. And beyond that, their families were business competitors, so they weren’t allowed to date. The moral of this story is that wonderful cliché that love conquers all, i.e., the Connor-Roddis union happened despite, not because of, their shared family legacies.

when Gordon Robert Phelps Connor asked Mary Roddis to marry him, she couldn’t —because they were in the eighth grade. And beyond that, their families were business competitors, so they weren’t allowed to date. The moral of this story is that wonderful cliché that love conquers all, i.e., the Connor-Roddis union happened despite, not because of, their shared family legacies.

Both of Sara’s parents spent their lives in the lumber industry, Gordon as president and chair of the board of Connor Forest Industries, and Mary as an author, speaker and advocate for legislation and education regarding multiple-use renewable forests. She was the first woman to be elected to the Wisconsin Forestry Hall of Fame, and she and Gordon are still the only married couple to have achieved the honor.

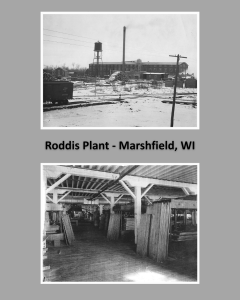

It was inevitable that Sara, too,  would have sawdust in her veins. One of her favorites of the many stories she holds, which she narrates in Wisconsin’s Flying Trees in World War II: A Victory for American Forest Products and Allied Aviation, is about the glue that helped win the war. It centers around the Roddis Plywood Corporation (RPC) having the only waterproof glue in the United States. This glue, purchased by Roddis in the early 20th Century from Germany, allowed RPC’s scientists from the Institute of Paper Chemistry in Appleton, WI to develop a similar recipe. Why was waterproof glue an integral part of Roddis’ aviation and marine plywood manufacturing? Because the glue that held the plywood wings on aircraft was casein-based, and it didn’t hold up well in humid environments. And when you’re in a war, you don’t want the wings falling off your aircraft!

would have sawdust in her veins. One of her favorites of the many stories she holds, which she narrates in Wisconsin’s Flying Trees in World War II: A Victory for American Forest Products and Allied Aviation, is about the glue that helped win the war. It centers around the Roddis Plywood Corporation (RPC) having the only waterproof glue in the United States. This glue, purchased by Roddis in the early 20th Century from Germany, allowed RPC’s scientists from the Institute of Paper Chemistry in Appleton, WI to develop a similar recipe. Why was waterproof glue an integral part of Roddis’ aviation and marine plywood manufacturing? Because the glue that held the plywood wings on aircraft was casein-based, and it didn’t hold up well in humid environments. And when you’re in a war, you don’t want the wings falling off your aircraft!

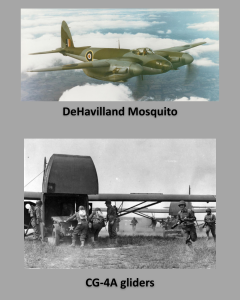

This glue kept the wings from falling off the “Wooden Wonder/Timber Terror” DeHavilland Mosquito, an immeasurable success at a crucial juncture in the war.

Connor describes the book as an “offshoot” of her work as director of education at the Camp Five Museum in Laona, Wisconsin, a museum founded by her parents (in a town founded by her grandfather). She created and curated the nationally traveling museum exhibit, “Wisconsin’s Flying Trees: Wisconsin Plywood Industry’s Contribution to WWII,” which was seen by more than 175,000 people.

While Connor claims she doesn’t have a photographic memory, she has spent many years combing through her family’s papers to understand their long contributions to the lumber industry and, by extension, the history of the United States. Working with a grant from the Hamilton Roddis Foundation (HRF) to the UWSP Archives and Research Center, Connor has donated a historical treasure trove to the university. The Roddis family papers document the men’s and women’s wartime work providing the plywood for the DeHavilland Mosquito and other Allied aircraft raids throughout Europe. The CG-4A Glider construction for D-Day with the 82nd Airborne Division (of which Connor is now an honorary member), 101st heroic actions, and other missions were made possible by Wisconsin’s forest industry. Even Howard Hughes’ “Spruce Goose” is made of Roddis plywood from Vilas County, Wisconsin.

the UWSP Archives and Research Center, Connor has donated a historical treasure trove to the university. The Roddis family papers document the men’s and women’s wartime work providing the plywood for the DeHavilland Mosquito and other Allied aircraft raids throughout Europe. The CG-4A Glider construction for D-Day with the 82nd Airborne Division (of which Connor is now an honorary member), 101st heroic actions, and other missions were made possible by Wisconsin’s forest industry. Even Howard Hughes’ “Spruce Goose” is made of Roddis plywood from Vilas County, Wisconsin.

Connor is not ready to rest on her already sizeable contributions to the history of Wisconsin and beyond through the lens of her fascinating family. She says the Forest History Association of Wisconsin, co-founded by Mary Roddis Connor, has a long-range ongoing project of working with UWSP to accumulate Wisconsin forest products’ industry history. The HRF, which has supported this effort, continues its enormous philanthropic legacy of Hamilton Roddis, and through the archival gift is hoping to create an exhibit at UWSP to include audio-visual artifacts, interviews, and photos of the extraordinary stories of “The Greatest Generation.”